Hot tips to bring the awesomeness of Visual Studio Code to Vim. Wouldn’t you know it, but the official prettier team has a vim plugin. Also, incredibly simple to set up. Are there any plugins for Visual Studio like EasyMotion, but without VIM? Question I want to learn VIM in the future, but am busy with a project right now and don't want the learning curve to interfere with my workflow. Open Visual Studio Code; Go to Extensions; Type vim in the search box; The first plugin named Vim is the one you want (VSCodeVim) Click on the install button; Epic Victory! This is how you install VSCodeVim. After Visual Studio Code finishes installing the extension, you may need to restart it for the changes to take effect.

Out of Date Notice (Nov. 2019): I now use Supertab instead of YouCompleteMe. I still use Omnisharp-vim but with the roslyn-based Omnisharp server instead of the mono one that was originally used by YouCompleteMe.

At work we’ve made the jump from back-end coding in Visual Studio and running our APIs on Windows with IIS to coding and hosting everything on Linux. We also switched from SQL Server to Postgresql. It took several months to complete the transition in steps, but we’re almost there. It can be done.

I Know What You’re Thinking

You’re thinking that you could never give up the luxury of Visual Studio. You could never survive without the convenience of Intellisense and autocomplete. Your life would be meaningless without your precious breakpoints and line-by-line debugging. You would shrivel up into a dry empty husk in the absence of ReSharper’s loving embrace.

Life with C# on Linux isn’t all that bad. You can still have many of the things you love about Visual Studio, without all of the bloat. The purpose of this article is to explain how I’ve achieved some of that for myself.

Why Make the Switch?

The reasons for phasing Windows and Windows-based tools out of our tech stack can, if you ask me (which you implicitly have by reading this article) be boiled down to “Windows sucks.” The primary motivating factor is that automatically provisioning Windows machines (being able to consistently spin up new instances and get your software and its dependencies installed and configured) is like trying to train a cat to use a human toilet. Sure, it can be done (I’ve seen videos), but it’s difficult, it’s unnatural, and people will think you’re not right in the head for even trying. The fact that Windows servers are typically more expensive (almost comically so when dealing with SQL Server) doesn’t help. Linux is just a cleaner solution for running server infrastructure. Microsoft is certainly headed in the right direction these days, and I have some confidence that they’ll get there eventually, but as it stands today Windows sucks as a server platform.

Windows Server 2012 uses their touch-screen optimized GUI, for goodness’ sake! Who thought that was a good idea? A server operating system doesn’t need a GUI to begin with let alone a poorly conceived tablet-optimized one.

In theory, even if you’re running your production environment on Linux and Mono, you could still choose to develop in Windows and Visual Studio—in my experience, situations in which you need to write code differently between the two platforms are pretty rare and easily avoided. There have been situations we’ve run into where Mono behaves slightly differently (usually in unexpected or broken ways), so if you take this approach it’s possible that you might miss problems with your code that exist in Mono but not Windows, so it’s important to write lots of tests and to run them using Mono prior to deploying.

I am a huge fan of Vim. When I was coding in Visual Studio I was using an extension called ViEmu which added Vim keybindings and features to the editor. The problem with ViEmu is it’s freakin’ expensive. I think I paid $100 up front for a license and then had to re-up my “subscription” a couple times for $50 when new versions of Visual Studio came out in order to get a new compatible version of the extension. I certainly don’t begrudge ViEmu’s creator for making money off his work, but paying hundreds of dollars to use features from a free open-source editor makes baby pandas cry. Add to that the cost of Visual Studio itself plus another “subscription” to ReSharper and you’re starting to reach levels of expense that simply don’t make sense for a solo indie developer (yes, I do this in my day job, but I don’t use the tools they provide for my personal/hobby work on the side). Visual Studio is also slow.

C# Autocomplete in Linux

The simplest option to get intellisense-like autocomplete functionality on Linux is to use MonoDevelop (or Xamarin Studio if you’re on OS X). Meet the new boss, same as the old boss. If you’re happy with a big all-encompassing development environment like this, more power to you! Heck, why not go one step further and use Visual Studio Code?

If you prefer to use your editor of choice (Emacs, Vim, Atom, etc.), you can probably also have autocomplete, it’s just a little more complicated to set up.

Visual Studio Code Best Vim Plugin

Omnisharp and Friends

Omnisharp is a mish-mash of open source stuff that adds .NET tooling to a variety of editors on Linux. For Vim, use your preferred plugin manager to install the Omnisharp-vim plugin. The readme covers the configuration changes and build process required. You will also need to install an autocomplete plugin—there are a few options listed in the readme but the one that I was able to get working is YouCompleteMe. Just make sure to include the --omnisharp-completer argument when running the install script.

I also installed dispatch.vim which will automatically enable the .NET tooling in Vim whenever you open a C# source file. If you didn’t install this, you’d need to manually start up the Omnisharp server and connect to it whenever you want your autocomplete. One downside of the automated method is that you can’t edit files from two separate solutions at the same time. Omnisharp runs as a server that parses your solution and project files, and the autocomplete plugins get their information by querying that server process, which means once that process is started for one solution, opening files from another solution will try to use autocomplete information from the first one. In theory you could work on multiple solutions simultaneously, but it would require manually spinning up and connecting to multiple instances of Omnisharp running on different ports.

Another nice benefit of Omnisharp-vim is that whenever you edit and save a new file, it will traverse up the directory tree and add that file to the first project it finds. That’s handy, but you still end up needing to manually modify csproj files in a lot of situations (adding or updating references, removing or renaming source files, etc.). If there’s something particularly tedious I need to do along these lines, I usually cave in and spin up a copy of MonoDevelop. I would, for example, want to gouge my own eyes out with a rusty spoon if I had to manually update a Nuget package across a couple dozen projects.

Debugging

If you want line-by-line debugging with breakpoints and watches and all that other stuff that you’ve probably become so dependent on in Visual Studio, your only options are MonoDevelop/Xamarin Studio or Visual Studio Code. Personally, I’ve eschewed debugging since making the move to Linux, relying instead on console output and throwing exceptions in my code to help track down tricky issues. At first I thought that this would be a deal breaker, but after several weeks I’ve found that it’s actually not that bad. Being able to set breakpoints and do line-by-line debugging isn’t as important as you think once you get used to life without them.

Testing

Visual Studio has some pretty nice test-running facilities built in. We use Xunit for all of our testing, so I would run all of our tests using the ReSharper Xunit runner. Now I run them all from the command line using the Xunit console runner. Works fine.

One gotcha to be aware of is that if you’re using Xunit 2.0, it doesn’t work in the current version of Mono. There is an outstanding issue in Xunit, but it’s actually due to a bug in Mono. The bug has been fixed, but we won’t be seeing it until Mono 4.2 is released. I have no idea when that will be (as of this writing Mono is at 4.0.3). Fortunately, we were still on Xunit 1.9 when we made the switch, so our tests run fine.

Continuous Integration

I’m going to get really esoteric here and talk about using Shippable to build Mono projects. Don’t do it! It is an exercise in frustration and futility. Something about their setup (which may actually be a larger issue with running Mono in Ubuntu in general) makes Mono unusable. You can read about some of my trials and tribulations in the issue I opened.

Conclusion

This article is a lot more rambly than I had intended, but hopefully I’ve achieved my goal of portraying the current state of working with .NET and C# in Linux as pretty far along—certainly far enough to work competently and comfortably on serious projects. We’re still finding new little bugs and issues in the Mono runtime itself that we have to work around, but no show-stoppers, and things are only going to continue to improve now that Microsoft has open-sourced the .NET runtime.

Short Permalink for Attribution: rdsm.ca/xrfs0

Comments

I started using Vim as my main editor around six months ago and I can say it hasbeen a worthwhile experience because it has pushed me to think in a moreefficient way when it comes to editing text.

This article explains my rationale for switching to Vim so, hopefully, it helpsyou make a decision on whether investing in learning Vim is justifiable for youtoo.

My history with text editors

I have tried a number of text editors since I first learnt to code just overthree years ago and I’ve had good experiences with each one for the most part.

I want to write a bit about those experiences so you can see where I’m comingfrom and understand how I came to using Vim eventually.

Sublime Text

The first editor I used was Sublime Text 3. Ichose it because it seemed to be really popular at the time amongst webdevelopers and most tutorials recommended it as a beginner friendly option.

At this point, I was only just learning to code so I only made use of its mostbasic features, although I did learn how to install plugins for addedfunctionality. Emmet was one of my favourites as it helpedme write HTML faster and that was just awesome.

I used Sublime for well over a year and even completed the Front-End certificateon freeCodeCamp doing all my projects within it. To be honest, I didn’t have anyreal problems with Sublime save for the popup that shows up every now and thenencouraging me to purchase the full version of the product.

To be sure, the free version is unrestricted in its feature set, but you justhave to deal with that popup and it can be annoying sometimes. As I didn’t have80 dollars to spend on a text editor, I began to look for alternatives.

First stint with Vim

Around this period, I decided to give Vim a go for the first time since it was always part of the conversation when you look at text editors for programmers and was favoured by many.

Vim was definitely more difficult to start with and although I was able to learn the basics, I just didn’t see why everything had to be so complicated.

I wasn’t productive at all so I gave up on Vim after messing with it for a while and decided to take a look at Atom instead which was closer to Sublime in terms of interface and workflow.

Atom

Switching from Sublime to Atom wasn’t difficult because Atom is largely inspiredby Sublime so they had a lot in common which made it really easy for me to startusing it.

All the plugins I used or an equivalent were available on Atom so I was prettymuch good to go from the start. As a result, I was able to get my work donewithout much fuss.

However, being built on Electron, Atom was having a huge impact on my RAM andCPU. As I had only 4GB of RAM at the time, this was significant to me andnecessitated an upgrade in that department which I effected by installing anadditional 4GB on my computer.

With Atom, performance was not as good as Sublime from the start. I was notsurprised by this since basically all other Electron apps I had tried had moreor less the same issues. Startup time on my PC was slow, but once it loaded up,it wasn’t too bad.

Overtime, I became frustrated at the lack of improvement in this area despitereceiving regular updates. So I sought a change all over again.

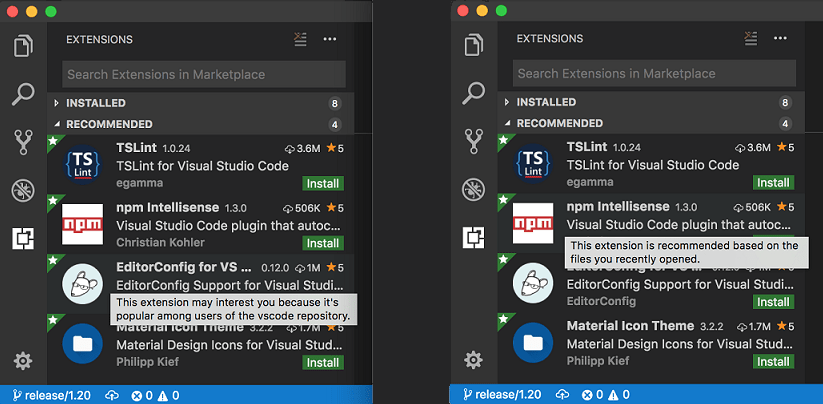

Visual Studio Code

Around this time, Visual Studio Code wasgenerating a lot of discussion in programming forums and had a lot of good presson various blogs. Since it was also built on Electron, I wasn’t expecting toomuch difference from Atom in terms of performance, but I gave it a whirl anyway.

I wasn’t too impressed at first; it didn’t seem to offer anything that I wasn’talready getting from Atom and performance wasn’t significantly better. So Iuninstalled it and stuck with Atom.

However, with each monthly release, there would be some hype, and I woulddownload it again and try it out. It always seemed to get better while Atom, incontrast, was stuck in a rot especially on the performance side.

Eventually, VS Code became clearly superior in feature-set and performance so Iswitched to it full-time. At this point, I deleted Atom from my Computer and VSCode reigned supreme.

Switching to VS Code from Atom was not as seamless as the switch from Sublime toAtom. This was partly because the interface was a little different and it tookme some time to adjust.

The default key bindings were also so much different from what I was used tocoming from Atom. This issue was easily solved by installing an extension thatremapped the key bindings to Atom’s so that eased my transition a bit.

VS Code is probably the best text editor for developers who write a lot ofJavaScript and TypeScript due to its comprehensive out-of-the-box support forboth languages. However, other languages are also well supported. It was reallyeasy to work with Rust for example, which Idabbled in sometime last year, with the help of some plugins.

In the months in which I used VS Code, I didn’t have much to complain about.Although performance wasn’t as good as Sublime, it was much better than Atom andcontinued to improve.

Despite this, I still had an eye on learning and using Vim. Any time I readabout text editors in a discussion forum like Reddit or Hacker News, someone isbound to sing the praises of Vim and mention how much it can improve personalproductivity.

When one of my friends switched toVim and soon after was singing thesame song, that did it for me. I just had to get what was so good about Vim.

Trying Vim for the second time

Since I didn’t have much going at the time, haven just released StellarPhotos, I decided to switch to Vim cold turkeymeaning I didn’t retain any other text editor on my computer during thistransition process in a bid to force myself to use Vim exclusively.

It certainly wasn’t as difficult as when I tried it the first time. I usedvimtutor to remind myself of the basic commands and just went from there.

Vim is bare bones and doesn’t come with all the features I had taken for grantedin other text editors, but in most cases, I could add the functionality I neededusing a plugin.

That said, this became problematic to some extent as it led me to install morethan what I actually needed and my .vimrc file was populated with a lot ofstuff that I didn’t understand.

So I took a step back and stopped trying to make Vim work like the other texteditors I had used and instead, learn the features it has that makes it sounique and special. It quickly dawned on me that Vim can actually do a lot onits own without plugins.

Vim Emulator

Where necessary, I could still add plugins but, by not using them to scratch myevery itch, I was forced to learn the Vim way of doing things which was, in mostcases, better than what I was used to.

Working with just the keyboard has been a real eye-opener to just how fast onecan be without touching the mouse. Everything can be achieved with just a fewstrokes, and due to Vim’s modal nature, each key combination has a differentmeaning in each mode. That may sound complicated on first thought, but it’sactually really intuitive once you get used to it.

I have adopted the mindset of preferring to just use the keyboard in other areasas well like using jumpapp for switchingbetween applications and using Saka Keyfor navigating quickly in my browser.

Update: I now use Surfingkeysinstead of Saka Key and Run or raisefor GNOME on Wayland.

One of the things I love about Vim is that each change can be repeated manytimes using the dot command or macros which does save me a lot of time whenediting code. It may just be seconds saved here and there but it adds up.

The one thing I’ve found significantly worse in Vim compared to other editors isthe colour and font quality, but I suspect this has more to do with my terminalemulator (I use Terminator).

I know its possible to make Vim look really good in the terminal as I’ve seenscreenshots of other setups on r/Unixporn,but I’ve not been able to create something I’m entirely happy with thus far soI’m currently exploring what Gvim (Vim GUI) has to offer.

Conclusion

Having spent six months using Vim as my main editor, I can say it has definitelybeen a worthwhile experience and I don’t see myself switching over to some othereditor anytime soon.

Right now, I’m looking to improve my mastery of the editor, and learn someadvanced flows to become even more efficient. To that end, I’m currently readingPractical Vim by DrewNeilwhich appears to be one of the best books on the subject.

If you already have a productive setup in your current editor, I don’t thinkit’s necessary to switch to Vim abruptly like I did. It may not even berealistic depending on your work situation.

Having said that, I think it is still useful to learn the Vim way of editingtext and you don’t need to use Vim itself to do so. Most editors have a pluginthat emulates Vim key bindings so you can easily experience the Vim way withoutthrowing away your existing workflow.

Here are the ones for Sublime,Atom, and VSCode.

Visual Studio Mac Vim Plugin

I will keep sharing what I learn on this blog, so if you’re interested inchecking out Vim, don’t be afraid to try it. You might just like it.